Did you ever notice how easy it is to figure out the right thing for someone else to do? I’m never at a loss for advice to give to someone who doesn’t know what to do. Amazingly, I’m often right! It isn’t that hard to look at someone’s situation fairly objectively and pick out the right course of action.

Of course, unsolicited advice is just that: unsolicited. Most people don’t actually want to hear my advice, right or wrong. Maybe they don’t know me, or don’t trust me, or maybe they are so preoccupied with the decision in front of them that they can’t even hear me. Whatever the cause, my words fall on deaf ears.

The word advice comes from (you guessed it) Latin: ad + visum, from videre “to see.” It means “guidance or recommendations offered with regard to future action.” In order to give advice, you have to see a little of what’s ahead, and give the person guidance to find success or avoid disaster as the case may be.

The real trick is to be able to give myself advice on doing the right thing. Every day we find ourselves making hundreds of small decisions in many areas of life. Each decision of itself is entirely inconsequential, but taken together, our decisions come to define us. Make mostly aggressive decisions, and you become aggressive. Make mostly self-centered decisions and you become selfish. You get the idea.

Spike Lee made a movie in 1989 called “Do the Right Thing,” describing one hot day in an urban neighborhood when racial tensions erupt. The day starts innocently enough, with a variety of odd and endearing characters waking up and going about their business. But hidden in their daily routines are racial prejudices and stereotypes built imperceptibly by thousands of little decisions that are subconscious. It takes only a few small misunderstandings, and tragedy strikes in the form of deadly violence. Spike Lee leaves it up to us to decide if anyone on that hot but otherwise normal day “did the right thing.”

My brother’s favorite poem, “If” by Rudyard Kipling, opens with the lines:

“If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you…”

Keeping your head is mostly a matter of perspective: it’s not always all about me; there are more important things in this world than just my own comfort or wealth or freedom or leisure.

Even when I know what the right thing to do is, it isn’t always easy to force myself to do it. It is hard to set aside my longing for what is comfortable or beneficial for me in order to do what is right, especially when it seems like no one is watching. In fact, since the solipsists believe that the self is all that can be known to exist, it follows that what is good for me must be the right thing to do, since I’m the only person that I can be sure of the existence of.

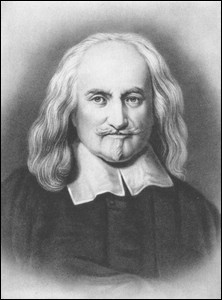

Thomas Hobbes wrote of a “natural state of man” in which everyone is completely free to selfishly pursue all of their own desires. This sounds enticing, but soon one man’s freedom tramples upon another man, resulting in "no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death: and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short."

Hobbes offers the idea of a “social contract” in which we give up a few of our personal freedoms in exchange for a society that allows us to safely exercise a host of other personal freedoms. The social contract theories of Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean Jacques Rousseau formed the philosophical basis for the American Revolution, ultimately finding their voice in Thomas Paine’s “The Rights of Man,” as well as the U.S. Declaration of Independence:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…"

It is interesting and challenging to think that our founding fathers, having decided that liberty was of paramount importance, proceeded to give up everything they had—property, livelihoods, even their very lives—in order to secure for all who came after them the very liberties that they themselves never knew. Somewhere in this irony lies the key to the concept of doing the right thing.

It seems that there are some things (the Declaration calls them “unalienable Rights”) which are so important, so critical to the human spirit, that to lose these things is greater even than losing one’s very life. Liberty is one of those things, as is freedom from tyranny. These are ideals that have a life of their own, and will be present in society long after each of us is gone.

Maybe that is one way to help me decide what the right thing to do is: if the decision pits my own interests against a larger, more universal, and more important ideal, then I should probably choose to deny some of my selfish interests and affirm the greater good. In my office I have 6 partners: I can either take advantage of them and always look to my own interests alone, or I can sometimes put the good of the clinic ahead of my own benefit.

If I only look to my own interests all the time, I reject the social contract, and I can expect my life to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short." Or I can “lay up treasures in heaven” by giving up some of my selfish ambitions in favor of what’s best in the long run. Ultimately, though, choosing against my own interests in favor of the greater good is only possible if I also believe that I will have to give account to God for everything that I’ve done.

The biblical book of Hebrews says “therefore, being surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses [the saints], let us…run with perseverance the race marked out for us.” We can deceive ourselves and pretend no one is watching while we choose the selfish way, but once we realize that Someone is always watching, it definitely makes it easier to Do the Right Thing.

1 comment:

Via email from my friend Stephen D:

Cool blog, Steve, I've actually considered starting one as well and just

not taken the time to start. Really fun to read your thoughts, though.

I found the quote at the end stimulating...

"If I only look to my own interests all the time, I reject the social

contract, and I can expect my life to be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish

and short." Or I can "lay up treasures in heaven" by giving up some of

my selfish ambitions in favor of what's best in the long run.

Ultimately, though, choosing against my own interests in favor of the

greater good is only possible if I also believe that I will have to give

account to God for everything that I've done. "

I agree with the strong contrast between selfish ambition - that natural

state of man - and the lifestyle demonstrated as we "lay up treasures

in heaven" - however, I'm probed to thinking as to whether the opposite

of the natural state of man is always the kingdom lifestyle of laying up

treasures. Between those two existences also lies one short of courage

and lacking selfish ambition but happily accomodating the crowd, living

for the moment and living to please those that surround rather than the

One above. This may be considered a type of selfishness - though it

could also be considered aimless selflessness.

The Rudyard Kipling quote is a great reminder for me as I study some of

the harder sections of the CFA...and I love thinking about Jesus and the

saints cheering us on.

I've bookmarked the site and look forward to reading more

Post a Comment