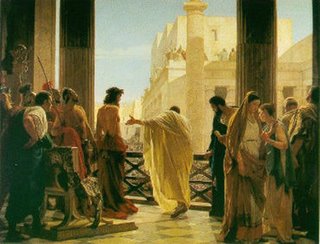

Pilate said to him, “what is truth?” (The Gospel of John, chapter 18, verse 38.)

We’ve been asking that question ever since. Lately, what with the demythologizers and the existentialists and the deconstructionists, the whole notion has gotten a lot foggier. The Oxford English Dictionary isn’t all that helpful either: it defines “the truth” as “that which is true as opposed to false.”

Going to the word “true” we get “in accordance with fact or reality; genuine; real or actual.” For you budding etymologists chasing word origins (as opposed to entomologists chasing little bugs around), the word is from Old English treawe, meaning steadfast or loyal.

Mark Twain popularized British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli's statement, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics." Having grown up in a household of 4 loquacious boys who preferred debate to fisticuffs, I know better than most that one can find statistics or facts to bolster even the most outrageous position.

“Mean Joe Green is the toughest defensive lineman in football.”

“Uh uh, Too Tall Jones is.”

“No way! Mean Joe hits harder cuz he weighs more.”

“Forget it! Too Tall is so tall, when he tackles you, he falls over on top of you and crushes you.”

“Does not!”

“Does too!”

“No way!”

“Way!”

At that point, the debate usually fell into ad hominem arguments, sometimes verbal, sometimes more physical (only to demonstrate for argument’s sake how Mean Joe actually hit or Too Tall actually fell on top of you). This phase of the debate rarely lasted very long, since my Dad usually resorted to the “Divine Right of Kings” argument to silence our debate.

“Shut up and sit down! You’re blocking the game.”

“Why should we?”

“Because I’m your father and I said so.”

Since that is a non sequitur that is unwise to attempt to breach, we usually sat down until the next infinitely important debate began minutes later.

It might be useful to review the various forms that bad arguments can take. I’m well aware of them since I’ve put all of them to fairly good use over the years. I have freely borrowed much of the following material from this critical thinking website.

Ad Hominem means “to the man” and refers to arguments, direct or indirect, that attack the person rather than their belief. Watch any political debate, and you’ll see mostly these body punches (often landing below the belt). “Candidate X wants to raise taxes because he is ignorant.”

Appeal to Authority: this might entail appealing to a famous person’s view, or a view on a certain topic by an expert in a different field. “Lindsay Lohan says that CO2 gas definitely causes global warming.”

Straw man: this refers to the ancient battle practice of placing dummies made of straw on the battlements of a castle to draw the arrows and spears of the enemy. This usually requires one to simplify and misrepresent the views of an opponent, making him an easy target to refute the simplified argument.

Argument from ignorance: here one asserts that X must be true because no one has yet proven it false, or the converse: that it is false because it has never been proven true.

Appeal to pity: playing on the feelings of the listener in order to win them to an otherwise poor argument.

Playing to the gallery: using an example, argument, or story likely to appeal to the observers, causing them to enter the debate (usually by applauding or disrupting the opponent’s speech).

Hasty generalization: an argument that generalizes from exceptional cases or creating a rule that fits the specialized case rather than the majority of cases. This is a favorite of bureaucrats. “A doctor was caught cheating Medicare, so now all doctors have to get fingerprinted.”

post hoc ergo propter hoc: the “false cause” argument where A supposedly causes B just because A precedes B. “Every time I sneeze, the door slams.”

Begging the question: assuming as a premise the very conclusion that we are trying to prove.

Irrelevant conclusion: in a long-winded argument, the actual conclusion being argued is different than the one that is supposedly being argued for. If you can’t dazzle them with your brilliance, baffle them with your BS.

False dichotomy: here, one argues that either X is true or Y is true. In reality there may be several other possibilities. This argument usually fails to consider all the available evidence.

Which brings us to the idea of critical thinking: not being critical, which usually involves finding petty faults or “picking” at someone, but thinking analytically about a topic. This usually involves an element of open-mindedness, some intellectual skepticism about the claims, ideas, or arguments, and an unwillingness to take things at face value.

Critical thinking asks several important questions about a claim:

Who is making the claim? This question helps you to identify the source of the claim.

What is the authority for the claim? This question will help you to identify whether the claim rests on opinion, prejudice, hearsay, evidence or whatever.

What evidence is there to support the claim?

How reliable is the evidence?

What other interpretations of the evidence might there be?

Thinking critically helps us assess the strengths and weaknesses of an argument, assumption, or idea. It’s too bad that most of what I’ve just presented is seen as hopelessly academic and theoretical by most people. Most television shows, popular books, and other media (not to mention far too many educational materials for our children) are composed of long strings of bad arguments connected together by bursts of uncritical thinking.

Critical thinking as I said requires some open-mindedness; not the sort of mushy, hyper-tolerant “big tent” blather that many liberal politicians spout, but a form of intellectual courage that decides to follow a sound idea wherever it goes, as long as it heads in the general direction of truth. It also usually requires a skepticism of “playing to the gallery,” straw man arguments, and false dichotomies often offered by politicians, editorialists, the clergy at their worst, and members of the press in the popular media.

Perhaps the most important aspect of critical thinking lies in an unwillingness to take things at face value. This is simply a disciplined form of intellectual curiosity. We actually learn it at a very early age with the “why?” questions. We often lose it just as quickly in early grade school, when our teacher shushes us for “talking out of turn.”

At its best, critical thinking should cause us to question standard operating procedures, outdated traditions, and "my way or the highway" leadership styles. It should also give us a healthy skepticism for "new and not improved" ideas, fuzzy logic, and fanaticism devoid of intellectual rigor. Heresy under the guise of "church tradition" on the one hand, or "progressive revelation" on the other is still heresy.

Failure to exercise this curiosity over a lifetime leads to a mindset that says, “we’ve always done it that way.” Or, “we’ve never done it that way.” This was the very problem that the Pharisees in Jesus’ day fell into: Jesus brought the truth in the form of “new wine” which didn’t fit well in their “old wineskin” thinking. The leaders failed to apply disciplined curiosity to the epiphany of the Messiah, choosing instead to make a desperate (and violent) stand on tradition. Ultimately, they were responsible for bringing Jesus before Pilate, resulting in the opening quote above.

Jesus himself claimed, “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” Truth, Jesus claims, is not a concept, but a person. Now that’s an idea we can sink our teeth into: let’s try using some critical thinking to assess Jesus’ truth claims about himself, his mission, and his place in our world. But that I will leave for another day.

No comments:

Post a Comment